https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/PHOTO-2021-12-09-13-58-10.jpg

1199

1600

Matteo Gecchelin

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Matteo Gecchelin2024-03-12 10:47:252024-03-12 12:22:22Alm Sweet Alm

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/PHOTO-2021-12-09-13-58-10.jpg

1199

1600

Matteo Gecchelin

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Matteo Gecchelin2024-03-12 10:47:252024-03-12 12:22:22Alm Sweet AlmMatteo Gecchelin

24 February, 2023

Two inconspicuous and unrecognizable little flowers – indistinguishable to unexperienced eyes and useless for ecological purposes – have created a perfect fairy-tale setting for plant science.

On a regular day in the late 1800s, Galinsoga parviflora – a small daisy-like plant of the grassy wastelands – arrived in Europe from Peru, probably transported as a seed by merchant ships. Since the European climate was suitable for its survival and reproduction, it did well in the old continent. It found itself so well there that it even began to colonize land that other species already occupied: it suffocated and eradicated them from their land. A true “alien” , a so-called invasive allochthonous species (e.g., a neophyte), occupied Europe.

All went well for parviflora, which took over any other competing species by expanding in vineyards and cultivated land. And yet… who lives by the sword, dies by the sword.

A distant South American cousin, Galinsoga ciliata, also reached Europe by sea in the early decades of the 1900s. In a new environment full of opportunities for expansion and reproduction, the two cousins declared war to each other because their land conquest plans were incompatible. Similarly, the two Galinsoga fought for supremacy in uncultivated areas, vineyards, grassy traffic circles, road dividers, and weeded field edges.

To date, Galinsoga parviflora seems to have been defeated in Trentino. Although it is not yet considered rare, it is definitely not easy to find. After having bitterly conquered its land, Galinsoga ciliata seems to have no fears of being overthrown.

In short, even the smallest and most insignificant plants, that we can hardly identify and recognize, know a lot about how to move, even without legs.

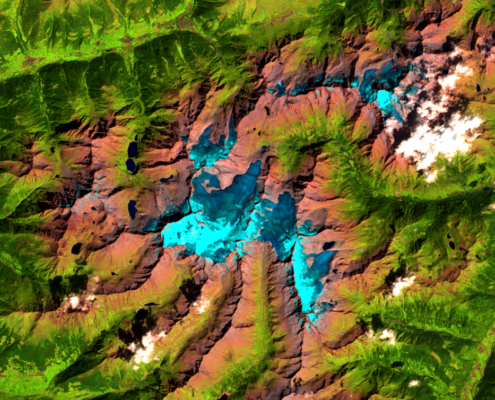

Fig. 1: Changes of the Alpine landscape terrain are already visible. Alpine species are moving, particularly upward and northward in search of coolness against global warming. However, this migration is not always straightforward. The journey is often impeded by terrain impediments or lack of soil. Photo by Author (Monte Pasubio, Trambileno – Trento, Italy. July 20, 2020).

In the last few days, an internationally resounding news in plant science burst out: the discovery by botanists at the Museo Civico di Rovereto of an orchid species altitudinal record. In summer 2022, Hammarbya paludosa was found in a peat bog at 1800 meters a.s.l. in upper Val di Non valley (Trento, Italy) [2].

In this case, the trigger and driving force for such displacements is environmental change: climate change firstly, but also changes in land use, changes in the designation of protected areas, water regime changes, agricultural changes and forestry tillage.

Although we now have a better idea of how many plant species are moving upwards to fight global warming in search of coolness, it remains unclear how many of these migrating species will successfully reach their destination [3].

Distribution simulations in the alpine areas of Veneto, Trentino, Alto Adige/Südtirol and Tirol carried out at the University of Innsbruck (unpublished), showed that by 2100 the occurrence of two shrub species, the Green Alder and Mountain Pine, will shift northward and to higher elevations. And yet the shift will be quite different region by region.

In Veneto, for example, some niches manage to reach higher elevations or move in latitude to the adjacent Alto Adige/Südtirol and Tirol. The ascent of many of them, however, is completely blocked or limited by the harshness of the Dolomites, which are too steep, inhospitable, rocky, and windy even for the most resilient individuals. And this is already noted by the locals and all the forests stakeholders of the area. Many of them already see a decrease of the two shrub species in the Belluno region. In contrast, the upward expansion of these two shrubs in Tyrol has been successful and made local breeders, farmers and foresters very worried.

In short, these plants know how to find their way forward, and rightly move – though perhaps unconsciously – in their own best interest. They are the green migrants we still know little about but that are increasingly becoming more present in our everyday lives. Even though the migration of a small greenish orchid may bother very few, it may interest thousands if olive trees, strawberries or grapevines moved.

Plants move and adapt and it is up to us to keep up with them. We must evaluate their changes and take advantage of their benefits to both humans and ecosystems. We should act as we have always done but aware that plants move and know their way forward.

Related articles:

References:

[2] Geppert, C., Perazza, G., Wilson, R. J., Bertolli, A., Prosser, F., Melchiori, G., & Marini, L. (2020). Consistent population declines but idiosyncratic range shifts in Alpine orchids under global change. Nature communications, 11(1), 5835.

[3] Gecchelin, M. (2022, 16 September). Even Plants Climb Mountains. Retrieved 13 February 2023, from https://greenmarked.it/even-plants-climb-mountains/

Cover- and preview image: Plants also get ready for migrating. They seek environmental and climate conditions more suitable for their survival. Image by Siriwan Srisuwan on Unsplash.

Preview image: Alpine species are moving, particularly upward and northward in search of coolness against global warming but with lots of impediments (Fig. 1).