https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bleachedcoral.jpg

768

1024

Paula Ruiz del Coro

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Paula Ruiz del Coro2024-07-01 22:02:332024-07-01 23:12:42The High Seas Treaty: Protecting Oceans’ Biodiversity

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Bleachedcoral.jpg

768

1024

Paula Ruiz del Coro

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Paula Ruiz del Coro2024-07-01 22:02:332024-07-01 23:12:42The High Seas Treaty: Protecting Oceans’ BiodiversityJanuary 22, 2024

Today I want to tell you a story. A story that begins with the most classic of introductions:

Once upon a time, there was a high Mountain covered with meadows and forests, with pastures and bare rocks, and furrowed by countless clear, cool streams. And on its summit, he wore a great hat. A very pure white hat of solid, unshakable ice.

And the Mountain was happy, aware that it was home and mother to all the animals and plants that found refuge there.

However, on a fine summer day, suddenly there was a great commotion. The Mountain found itself shaken, awakened in great turmoil by an incessant uproar. A battle had begun on right above it. And never would the Mountain have expected it.

The challengers were its greatest guests: Mrs. Forest and Mr. Meadow. This battle soon took the name “Kampfzone” and, unexpectedly, was won not by either Forest or Meadow but by a third, unstoppable challenger: “Krummholtz”!

The main characters of the story introduce what happens incessantly in our mountains from an ecological point of view, particularly in the Alps. I have always been fascinated by the idea of a kind of battle between the different components of an ecosystem for survival and dominance over the “opponent”. Indeed, even in a romanticized way, the challenge between forest (present at lower elevations) and the natural high-altitude grasslands is a real fact, and the Krummholtz are none other than those twisted shrubs, shaped by the continuous action of wind and snow, that are established right on the margin line between the subalpine forest and grassland formations: the Kampfzone, or “battle zone”.

What does this have to do with the climate and the people who inhabit the mountains?

This Kampfzone is the most obvious surface that can be found in the alpine ranges. Difficult to interpret, but relatively easy to spot, even from aerial and satellite observations [1].

Moreover, this margin zone, which varies in width, density of shrubs and trees, and vegetation dynamics, is the most complex surface that can be found in the Alps from an ecological point of view, as it is governed by processes induced by delicate balances.

In the last two decades, the trend of this line is to migration. And the concauses are as much natural as anthropogenic. A migration that, to tell the truth, is not a new fact for this ecosystem, which has been shaped by human action for centuries.

As early as the 17th century, through intense deforestation actions, this margin line was lowered from its real natural elevation, thus artificially creating meadows and pastures for agriculture and livestock management. Subsequently, after World War II, the economic-social situation in the Alpine valleys changed, resulting in a rapid loss of interest in the care and exploitation of high-altitude pastures and meadows, triggering a process of gradual recolonization of the forest toward higher altitudes. In short, a revenge of nature over man [2].

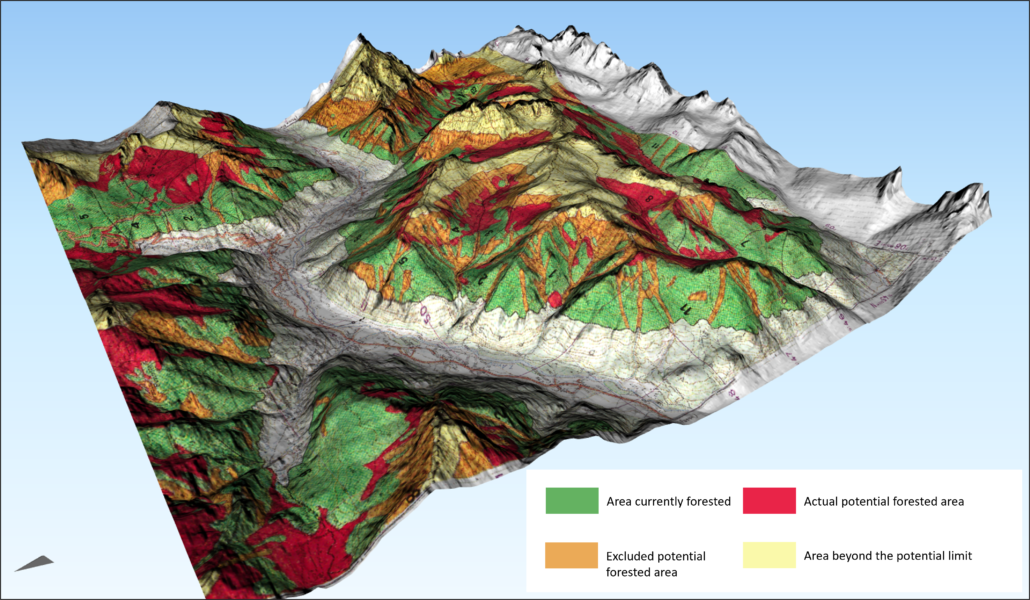

Fig. 1: Potential forest boundary. Sheet #12 – CANAZEI. Own 3D processing. Source: [2]

However, this revenge of nature, though constant since the 1950s, is actually turning out to be a little too pro-nature, especially in unexpected ways.

While it is true that forest growth is something positive, one must necessarily consider it at the expense of what this growth is taking place. The map in Fig 1 shows how the forest line (which we can understand here as the Kampfzone) appears to be highly variable as a function of the anthropogenic logging actions, with the areas in red and orange representing the surfaces that could potentially be occupied by the forest but is still not recolonized.

Such dynamics turn out to be very different to date. There is indeed a general increase of forest formations at the expense of high-altitude grasslands, but the key point is to understand how this elevation is or is not also followed by an elevation of the lower limit of the forest, i.e., that at the edge with the valley floor.

In short, where are these forests going?

The answer to this question – as usual for many ecological issues – is that it depends. It depends on the type of species characterizing the forest formations, the geographic area, the socio-cultural and economic dynamics of the territory, and the methods of analysis. In general, however, it can be considered how, for the Alps, the upward trend of spruce-fir forests, expanding to higher elevations but also shifting its presence from the lower limit, represents one of the dynamics of greatest impact on the reality of these territories, and not only in purely ecological terms.

The economic and cultural dependence established with this species over the past century [3] has meant that much of the forest land, at least in the Eastern Alps, is occupied by it. An increase in the elevation of the species, such that it is presented beyond the current (even potential) limit of the forest, and a simultaneous loss of the species at the lower elevations, which are more accessible, mechanizable, and therefore easier to use, also necessarily obliges a change of strategy towards harvesting and silvicultural techniques for the future. Just as with Spruce, this is also the case for many other species that modify, expand, and reduce their range of presence, making mobile and transformative what we have hitherto made and credit immutable [4].

In this, too, we are closely affected by climate change, which is as evident in the mountains as it is in the city and is forcing us to alter our plans for a future different from the one we had planned.

References

Click here to expand the references[1] L. Dinca et al., “Forests dynamics in the montane alpine boundary: a comparative study using satellite imagery and climate data,” Climate Research, vol. 73, no. 1-2, pp. 97-110, 2017.

[2] P. Piussi, Carta del limite potenziale del bosco in Trentino, Trento: Provincia Autonoma di Trento. Servizio Foreste, Caccia e Pesca, 1992.

[3] M. Cerato, Le radici dei boschi. La questione forestale del Tirolo italiano durante l’Ottocento, Publistampa Edizioni, 2019.

[4] S. Noce, C. Cipriano and M. Santini, “Altitudinal shifting of major forest tree species in Italian mountains under climate change,” Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, vol. 6, 2023.

Related articles:

Cover- and preview image: Forests, meadows, pastures and villages in Neustift im Stubaital (Tirol, Austria). Photo: Author. 07.11.2022