https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/cows-358959_1280.jpg

960

1280

Etienne Hoekstra

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Etienne Hoekstra2023-12-22 11:44:132024-05-16 10:23:40Sustainability Implications of Dutch Far-right Victory

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/cows-358959_1280.jpg

960

1280

Etienne Hoekstra

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Etienne Hoekstra2023-12-22 11:44:132024-05-16 10:23:40Sustainability Implications of Dutch Far-right VictoryApril 21, 2023

The word “drought” has recently returned to our vocabulary. First used sporadically, it is now becoming almost a daily recurrence. We hear it in news reports, social media posts, and exclamations and mutterings of people near lakes, rivers or streams. As GreenMarked, we have written about it in the past (The Aftermath of Exceptional Droughts; How much water does your 24-hours day consume?) and will continue doing it in the future.

Nonetheless, it seems that Italians’ awareness of droughts is not very high. In mid-2021, a poll by Ipsus reported that only 20 % of the Italian population is concerned about the state of water resources. Moreover, 70 % of respondents considered drought as an exclusive issue of specific areas or times of the year. The most significant number of concerned citizens was in Southern Italy, where 25 % of the population is aware of the problem. In the Northwest, the percentage is 16 %, 19 % in the Northeast, and 22 % in Center Italy [1].

And yet, according to the Environmental Protection and Research Center (Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale – “ISPRA”), the inhabitants of northern and central Italy are those who have to worry the most about droughts. Following a low precipitation winter, the Po River, Eastern Alps, and Northern and Central Apennines hydrographic districts are registering MEDIUM water severity levels. In other words, the seasonal flows are lower-than-average, water demands are higher-than-standard, and water reservoirs cannot guarantee a regular delivery rate. Consequently, there is a high risk of economic losses and impacts on the environment. Conversely, the hydrographic districts of the Southern Apennines, Sicily and Sardinia showed LOW water severity levels at the beginning of April, and water demand was still met [2].

The district water severity level is given by the level average of many water bodies in the district. The Po River district, for example, has a medium water scarcity level that has been calculated from average monthly flow values reporting a condition of “severe” and “extreme” drought [2]. The same happened in the Eastern Alps district this winter. The Adige, Brenta-Bacchiglione, Livenza, Piave and Tagliamento river basins have recorded water severity levels corresponding to “moderate and severe drought”, and yet, at the district level, the average value corresponded to “medium water severity level” [3].

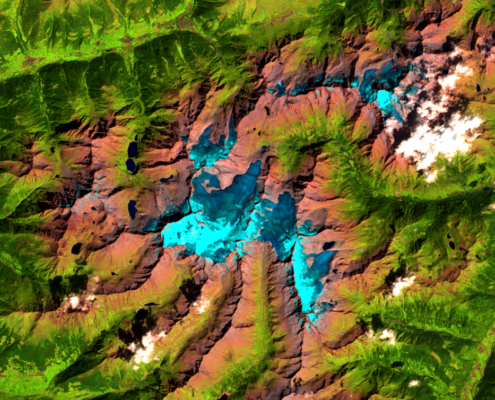

Fig. 1: Map illustration of the water scarcity levels in Italy. Image by GreenMarked. Data by ISPRA [2].

The other side of the coin is extreme precipitation events. Especially in summer, droughts are characterized by high temperatures and long periods without rain, and they are interrupted by severe thunderstorms that cause extensive economic-social and environmental damage. Damages are related to the rainfall intensity and excessive runoff, which often causes flooding and hydrogeological disruptions.

The perception lack of droughts increases the danger related to hydrogeological risk, which affects 94 % of the Italian municipalities. “More than 8 million people live in areas of high danger, often not being aware of it”, reported the Director of the National Association for the Management and Protection of the Territory and Irrigated Waters (“ANBI”). “This lack of knowledge is often an exacerbating factor when it comes to emergencies” [4].

It is, thus, necessary to continue to talk about droughts, extreme events, and the climate crisis to increase people’s awareness and make citizens ready, trained, and able to deal with emergencies.

However, treating droughts as an emergency and merely considering it in the short term is a serious mistake. The models and data acquired by the authorities depicted a situation that needs to be addressed with a medium-to-long-term strategy. Only by doing so, we can adapt to the climate crisis, manage the available water resource to the best, and make the water network as efficient as possible [5].

This article is part of the project “PILLOLE D’ACQUA PIANA: seminari itineranti, blog e podcast per una gestione sostenibile delle risorse idriche in Piana Rotaliana” carried out by ECONTROVERTIA APS and supported by Fondazione Caritro (Prot. no. U445.2023/SG.386 of April 23, 2023).

Related articles:

References:

[1] Ansa, R. (2021, June 17). Solo 2 italiani su 10 preoccupati per le risorse idriche. ANSA.it. https://www.ansa.it/canale_ambiente/notizie/acqua/2021/06/17/acqua-solo-2-italiani-su-10-preoccupati-per-risorse-idriche_5b1a5c02-e75b-4d3a-8b6c-968047d91c22.html

[2] ISPRA: Idrologia, Idromorfologia, Risorse Idriche, Inondazioni e Siccità. (n.d.). https://www.isprambiente.gov.it/pre_meteo/idro/SeverIdrica.html

[3] User, S. (n.d.). alpiorientali – Osservatorio Permanente.

http://www.alpiorientali.it/osservatorio-permanente.html

[4] La mancata percezione aumenta i pericoli. Nonostante la siccità l’italia è ad alto rischio idrogeologico. Il consiglio di ANBI per le vacanze “Dedicate qualche ora a togliere i ricordi dagli scantinati.” (2022, August 09) www.anbi.it. Retrieved April 16, 2023, from https://www.anbi.it/art/articoli/6752-la-mancata-percezione-aumenta-i-pericoli-nonostante-la-sicci

[5] Siccità: Situazione peggiorata nel bacino del Po. (2023, April 13). www.anbi.it. Retrieved April 16, 2023, from https://www.anbi.it/art/articoli/7288-siccita-situazione-peggiorata-nel-bacino-del-po

Cover- and preview image: Low water level in the Reno River, Province of Bologna, Italy. Photo by Author. April 18, 2023