https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Cattura-1.jpg

880

1618

Sarah Santos Ferreira

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Sarah Santos Ferreira2024-07-16 18:56:142024-07-16 19:45:21Three Environmental Initiatives Making a Difference in Brazil

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Cattura-1.jpg

880

1618

Sarah Santos Ferreira

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Sarah Santos Ferreira2024-07-16 18:56:142024-07-16 19:45:21Three Environmental Initiatives Making a Difference in BrazilOctober 28, 2022

As the second round of the Brazilian presidential election approaches, the fight against fake news and the publication of public data on social media is growing exponentially. In this article, we review some environmental key facts that took place during Jair Bolsonaro’s four year mandate.

Attempt to Remove the Ministry of the Environment

In 2018, Bolsonaro’s government did not present any specific environmental management plan, much less a strategy to tackle the Amazon deforestation or implement the Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Deforestation in the Legal Amazon (“PPCDam”). Instead, it tried to remove the Ministry of the Environment (“MMA”: is one of the public agencies in charge of the PPCDam and the protection of the Amazon), and merge it into the Ministry of Agriculture, claiming that they were “inefficient and did not serve the legitimate interests of the Nation” [1]. The proposal was never really implemented, but since then the MMA had to face tough operational challenges. Its Conservation and Sustainable Use of Biodiversity and Natural Resources program was cut by 139 million reais and its servers operating hours were constrained through an amendment of the Portaria no. 491 environmental law [2].

As reported by the Amazônia Real portal, this and other political maneuvers facilitated criminal activities in the jungle because environmental inspections and law enforcement was restricted to office hours. Environmental protection officers operating outside legitimate hours risked administrative proceedings, punishments and warnings, and their own life.

Deforestation Increase in the Amazon

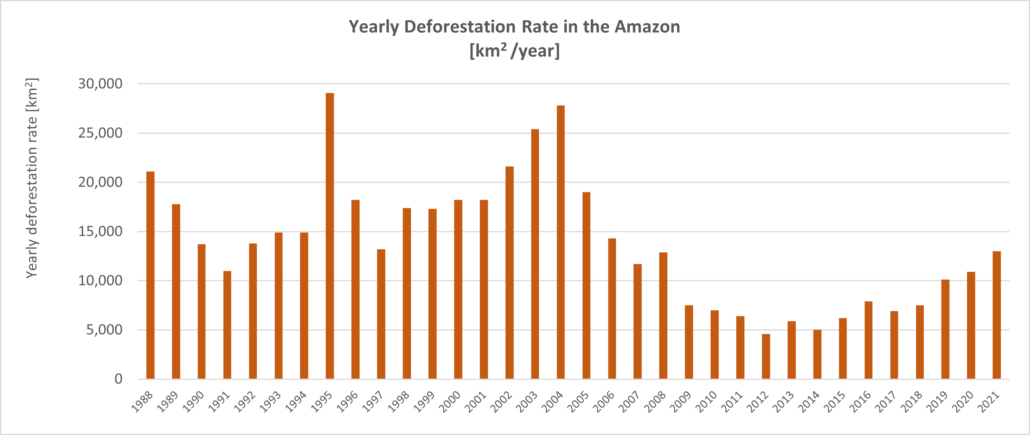

Despite Bolsonaro’s allegations that deforestation decreased during his government, current data from the National Institute of Spatial Research proved the opposite (Figure 1). Since 2018, the deforestation rate has grown by 73 %, passing from 7,500 km² in 2018 to 13,000 km² in 2021. Conversely, during Lula’s (Luís Inácio Lula da Silva) mandate, the deforestation rate had decreased by 67 %, going from 25,400 km² in 2003 to 4600 km² in 2011 [3].

Fig. 1: Deforestation rates in the Amazon (“Amazonia legal”) from 1988 to 2021 [3].

More Freedom to Land Owners

The current government increased the freedom of land owners and reduced the degree of State interference on farms:

“The State must make it easier for the farmer and their families to be the managers of the rural; identify which are the areas where it really needs to be present, and at what level.”

A Growing Threat to Indigenous Areas

Two delegates of Bolsonaro were put at the head of the National Indigenous Foundation and the Ministry of Agriculture: Marcelo Xavier and Nabhan Garcia, two ruralists that strongly support agribusiness.

In April 2020, the newly approved Normative Instruction no. 9 left non-homologated indigenous areas (i.e., lands with a marked physical border not yet validated by a Federal Decree) unprotected [4]. Two years later, 415 farms, equivalent to 239,000 hectares, had been registered within non-homologated indigenous land [5].

Fortunately, in 2021 the Federal Public Ministry suspended the Normative in several Brazilian states because it violated the constitutional rights of indigenous peoples, favored the illegal occupation of public land and caused agrarian conflicts [6]. Since then, several reports and demonstrations denounced how the government was threatening the lives of indigenous people, and, consequently, threatening several areas of environmental protection within indigenous land or land inhabited by indigenous people [7].

Hampering Family Farming

While agribusiness and illegal mining activities expanded at the expenses of deforestation and indigenous lives, family farming was severely hampered under Bolsonaro [8]. Public policies that ensured the sales and distribution of family farming products all over Brazil were modified and funding was drastically reduced. While agribusiness products are intended for export, family farming feeds a large part of the Brazilian population. Since family products are supplied in a multitude of public institutions, educational and health care centers, damaging family farming generated hunger in the country.

Violence Increase in the Amazon

In the last four years, the Amazon has seen an intensification of violence; especially murders in the states of Amazonas, Pará, Roraima, Amapá, Espírito Santo, Rio de Janeiro and Pernambuco [9]. Amazonas, in particular, has been stage of tragic stories, such as the murder of two important environmentalists on the fight for indigenous people rights: Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira [10].

Related articles:

References:

[1] Tribunal Superior Eleitoral – TSE. Jair Bolsonaro’s government proposal in 2017. Retrieved on 19 October 2022 from https://divulgacandcontas.tse.jus.br/candidaturas/oficial/2018/BR/BR/2022802018/280000614517//proposta_1534284632231.pdf

[2] Câmara dos Deputados – Plano Plurianual do governo Bolsonaro. Distribution of resources allocated to the main federal government programs in the 2016 and 2020. Retrieved on 19 October 2022 from:https://www.camara.leg.br/internet/agencia/infograficos-html5/ministerios/index.html#text16

[3]Biernath, A. 2022, October 17. Bolsonaro ou Lula: em qual governo a taxa de desmatamento na Amazônia foi maior? Retrieved on 28 October 2022 from: https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-63290268

[4] FUNAI – Fundação Nacional do índio. Terras indígenas – Definition and status of indigenous lands in Brazil according to FUNAI. Retrieved on 23 October 2022 from : http://sii.funai.gov.br/funai_sii/informacoes_indigenas/visao/visao_terras_indigenas.wsp

[5] Fonseca, B., Paes, de F. C., Oliveira, R. (2022, July 19). Governo Bolsonaro certificou 239 mil hectares de fazendas dentro de áreas indígenas. Retrieved on 23 October 2022 from: https://apublica.org/2022/07/governo-bolsonaro-certificou-239-mil-hectares-de-fazendas-dentro-de-areas-indigenas/#TerrasInd%C3%ADgenas

[6] Ministério Público Federal. Procuradoria – Geral da República (2021, July 30) Normativa da Funai que fragiliza proteção de terras indígenas está suspensa em 8 estados da Federação. Retrieved on 23 October 2022 from: https://www.mpf.mp.br/pgr/noticias-pgr/normativa-da-funai-que-fragiliza-protecao-de-terras-indigenas-esta-suspensa-em-8-estados-da-federacao

[7] COIAB – Coordenação das Organizações Indígenas da Amazônia Brasileira. Documents: Reports and repudiation notes. Accessed on 23 October 2022 from: https://coiab.org.br/documentos

[8] Siqueira-Gay, J., Sánchez, L.E. 2021 – The outbreak of illegal gold mining in the Brazilian Amazon boosts deforestation. Reg Environ Change 21, 28. Retrieved on 25 October 2022 from: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-021-01761-7

[9] IPEA – Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada. 2021. Atlas da Violência Completo. Retrieved on 23 October 2022 from: https://www.ipea.gov.br/atlasviolencia/arquivos/artigos/5141-atlasdaviolencia2021completo.pdf

[10] Wright, G. (2022, June 24). Bodies of Dom Phillips and Bruno Pereira returned to families. Retrieved on 28 October 2022 from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-61919244

Cover- and preview image: Brazilian protesters demonstrate in front of the National Congress Palace in Brasilia, 2016. Free-source photo by Agência Brasil Fotografias, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=47526116