https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Cattura-1.jpg

880

1618

Sarah Santos Ferreira

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Sarah Santos Ferreira2024-07-16 18:56:142024-07-16 19:45:21Three Environmental Initiatives Making a Difference in Brazil

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/Cattura-1.jpg

880

1618

Sarah Santos Ferreira

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Sarah Santos Ferreira2024-07-16 18:56:142024-07-16 19:45:21Three Environmental Initiatives Making a Difference in BrazilApril 05, 2024

Continuing the series of articles on Brazilian biomes, I invited Professor Francisca Soares de Araújo, a biologist with a Master’s Degree in Botany and a PhD in Plant Biology, to discuss the challenges of the Caatinga and its inhabitants in the face of climate change. In this conversation, we revisited the biome’s history from a local perspective and talked about the danger involved in the new vegetation dynamics of the Brazilian semiarid region.

Tell us a bit about the history of neglect of the Caatinga.

The [Brazilian] semi-arid climate […] is one of the poorest regions in a developing country. As a result, we had fewer universities and consequently fewer researchers. From the 1990s onwards, we saw an increase in researchers in the region due to the expansion of universities, which began in 2002 with the center-left government in Brazil […]. I’m not endorsing any political party, this is a fact […] to give you an idea of where I was born, electricity only arrived in the last 10 – 15 years. Without electricity, you cannot access communication means like TV, phone… The Caatinga biome corresponds to 11% of the national territory, encompassing 28 million inhabitants. And the question now is what do you do with them?

In your perception, is the Caatinga still a little-known biome?

No, we already have a lot of scientific information; what I notice is that this information is not reaching decision-makers, and that’s the big problem. […] Isolated initiatives from institutions and NGOs do not generate significant impacts to popularize this knowledge. There is a need for government programs on a national scale [for] this knowledge to reach society and change the way natural resources are used, at all levels, all social classes. Because nationally, we are major exporters of agribusiness, agriculture, soy, and food [but] at very high costs of land degradation. The Northeast is not a major exporter because there are production difficulties, but the Northeast uses the land similarly to other biomes with more humid climates, however, we don’t have water [for that].

Fig. 1: Screenshot of the conversation between the Author and interviewed via Zoom. Reproduction authorized.

What impacts of climate change have you identified on the biodiversity and ecology of the Caatinga?

The increase in temperature and decrease in water mainly affect small animals and plants. Plants have roots, they are fixed, therefore […] they cannot migrate. However, our studies indicate that most of the plants inhabiting the Brazilian semiarid region today will expand their distribution area. This may seem good, but it is not. These plants are smaller, deciduous and [have] thinner leaves. Producing leaves is costly for plants that need water, nutrients, and light. Larger trees, with thicker leaves and greater carbon sequestration potential, will be restricted to mountainous regions, which are small areas in the Brazilian semiarid region. This means that the wetter areas we have in the Caatinga today will become drier. Overall, we will have a loss of biodiversity. At the feet of the mountains, which are the wettest regions, we have the sources of the hydrographic basins, so this will have a huge impact on water availability for humans.

What are the main challenges of the Caatinga in the face of global warming?

The main challenge is a change in land use culture. Because most farmers and livestock farmers use the land as if we were in a climate without water restrictions – which will increase even more with global warming. It’s not [a climate] suitable for raising large animals. And there are livestock farmers who want to irrigate pastures. [We need] this change in land use culture and a planned action that integrates permanent preservation areas, currently only 20% like the Cerrado. We have to think about crops that are not irrigated and that can produce in a short period of rainfall, which will decrease even more, and in the raising of small animals. From a conservation standpoint, to minimize desertification, we need to restore the hydrographic basins and reforest them. Because historically [these areas] were the first to be deforested and degraded. [The ideal would be] to integrate: permanent preservation areas (APPs), legal reserve areas, areas to be restored, and public areas of environmental preservation to minimize desertification. The Caatinga is one of the least protected biomes. The government’s goal is to protect 30% of each biome by 2030, but the Caatinga doesn’t even have 10%. It’s possible to minimize the impacts, but not to reverse them. [Apart from all this] we should also make cities friendlier, with tree planting, alternative constructions, and better use of wind. This has to be a national initiative involving state and local governments.

Reading suggestions from the expert

Carvalho, C. E., Sfair, J. C., Eller, C. B., Menezes, B. S., Menezes, M. O. T., & Araújo, F. S. (2023). Tree height, leaf thickness and seed size drive Caatinga plants’ sensitivity to climate change. Journal of Biogeography, 50(12), 2057-2068. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.14717

Xavier, S. A. S., Araújo, F. S. de, & Ledru, M. P. (2022). Changes in fire activity and biodiversity in a Northeast Brazilian Cerrado over the last 800 years. Anthropocene, 40, 100356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ancene.2022.100356

Related articles:

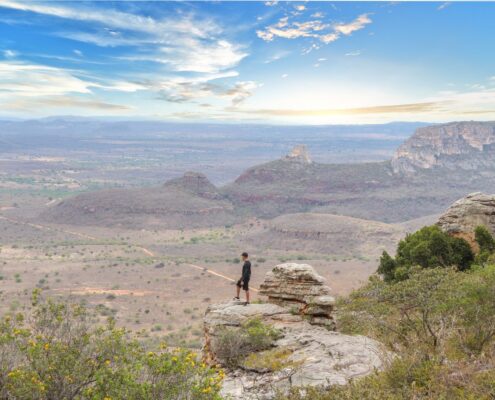

Cover- and preview image: Caatinga during the dry season. 2019, taken by Victor Gonçalves