https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/DiegoSaldanhaInstagramfeed-1-scaled.jpg

1714

2560

Barbara Centis

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Barbara Centis2024-07-26 17:27:232024-07-26 17:29:54The Unbearable Weight of the Fishing Industry

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2024/07/DiegoSaldanhaInstagramfeed-1-scaled.jpg

1714

2560

Barbara Centis

https://greenmarked.it/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/LOGO-GREENMARKED-SITO-600x600.png

Barbara Centis2024-07-26 17:27:232024-07-26 17:29:54The Unbearable Weight of the Fishing Industry29 January 2020

Plastic pollution around the world

The United Nations (UN) identified plastic pollution as one of the world’s biggest environmental challenges (UN Environment Programme, 2018), and embedded it in the Sustainable Development Goal 14: “Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources” (UN, n.d.).

Plastic pollution in oceans was first documented in the 1970s. In 2010, Jambeck et al. (2015, p.768) estimated that “275 million metric tons of plastic waste was generated in 192 coastal countries […] with 4.8 to 12.7 million [metric tons] entering the ocean”, thus affecting all major ocean basins (Geyer et al., 2017). In addition, ocean currents can form extensive plastic fragments such as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch (GPGP), which is supposed to cover a surface area triple the size of France (Lebreton et al. 2018).

From the 6.3 million metric tons of plastic waste that had been created in 2015, “around 9% of which had been recycled, 12% was incinerated, and 79% was accumulated in landfills or the natural environment” (Geyer, Jambeck & Law, 2017, p.1). If the situation remains unchanged, the amount of plastic waste gathered in landfills or the natural environment will more than double by 2050 (Geyer et al., 2017).

The Ocean Cleanup

Tackling these issues requires social entrepreneurship, meaning the skill to seek changes and turn issues into opportunities (Dees, 2001). Boyan Slat, the initiator of The Ocean Cleanup (TOC) project, took the opportunity to create value from cleaning up parts of the ocean that are contaminated by plastic and other kinds of waste. His idea became a pioneer project and inspired hundreds of people around the world (TOC, n.d.A).

TOC has been developing a technology that could passively collect half of the Pacific Ocean plastic waste within ten years. “Passively” means that the heavy work is delegated to ocean currents, while an artificial, floating coastline actively captures the plastic. Marine life fishes can swim under the floating barriers placed in a V-shape. The barriers carry the collected plastic to a central point where ships are able to remove the plastic from the water, and transport it to the mainland for recycling. (Rijksoverheid, 2016; TOC, 2020A).

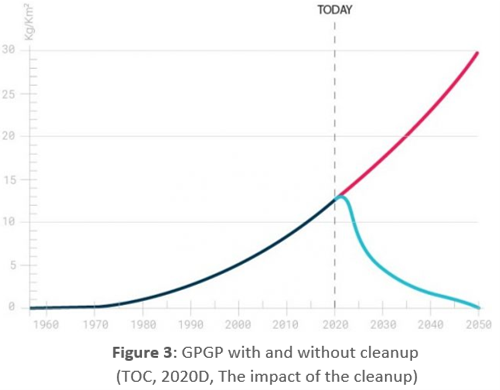

The aim of the project is to clean-up half of the GPGP before 2025, and the remaining half before 2050. The aim can be visualized in Figure 3, together with a scenario of no-action. Although the figure is limited to the GPGP, TOC has equal long-term goals for other ocean garbage patches. For example, TOC aims to reduce the amount of ocean plastic with 90% by 2040 (TOC, 20202D; TOC, n.d.C). If TOC’s operations were complemented by a considerable reduction of plastic sources on land, a plastic-free ocean could be accomplished by 2050 (TOC, 2020C). However, this requires “radical changes at the individual, corporate, and governmental levels of society” (TOC, n.d.C).

Criticism

Despite the ambition to accomplish a plastic free ocean and the received recognition, the TOC project has received criticism as well. Van Franeker & Kühn (2018) reviewed the impact of TOC operations and concluded that if TOC indeed managed to clear half of the GPGP by 2025, it would only remove about 0.1% of the plastic that ends in the ocean every year. Likewise, many scientists stressed that the plastic sources reduction is in fact the most effective mitigation strategy (Rochman; Sherman & Sebille, 2016). Although TOC acknowledges source reduction as important, it does not see it as the solution to current ocean plastic pollution issues (TOC, 2015).

Furthermore, Sherman & Sebille (2016, p.2) declared that “ocean plastic removal might be more effective […] closer to shore than inside the plastic accumulation zones in the centers of the gyres”, like the GPGP. TOC, instead, focuses on ocean garbage patches in high seas gyres “because the plastic floating outside of these ocean garbage patches either naturally removes itself from the ocean by beaching onto a coastline, or eventually also ends up in an ocean garbage patch” (TOC, n.d.B).

Moving forward

To move beyond its first testing and 2015 prototype phase, TOC conducted a feasibility study. Costs were covered with a crowdfunding campaign that raised $100,000. The study included topics such as engineering, oceanology, ecology, maritime law, finance and recycling, and was conducted by a voluntary collaboration of more than a hundred private citizens, organizations and institutions (Slat et al., 2014). The favorable outcome illustrated the sustaining aspect of the innovation.

The positive media coverage that came with the favorable feasibility study was used for the second crowdfunding campaign. This campaign raised over 2 million dollars, becoming the most successful crowdfunding campaign opened by an NGO, so far (TOC, 2015; ABN AMRO, 2014). It allowed TOC to develop and test different prototypes in different locations (TOC, 2020A).

In late 2016 TOC initiated another fundraising round. In May 2017, it issued a press release stating that it “successfully raised 21.7 million USD in donations since last November [bringing TOC’s] total funding since 2013 to 31.5 million USD, [which enables TOC] to initiate large-scale trials of its cleanup technology in the Pacific Ocean” (TOC, 2017). The fact that this latter funding round comprised solely on donations demonstrates the legitimacy perceived by the initial investors that supported the project.

Eventually, after “hundreds of scale-model tests, a series of prototypes, research expeditions and multiple iterations”, a first full-scale clean-up system was ready in 2018 (TOC, 2018). The unique business approach of TOC, however, also created legal complications that had to be solved before the full-scale system could be launched. To overcome these hurdles, TOC signed a covenant with the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management (MIW, 2018). With an applicable legal framework and support from the Dutch government, TOC was ready to launch its first full-scale clean-up system. The aim of the operation was to test the system and collect relevant data while cleaning up the GPGP (TOC, 2018). Nevertheless, the operation was prematurely terminated because the system was not able to actually capture the plastic due to “an inconsistent speed difference between the system and the plastic” (TOC, 2020A, p.17). This led to a systematic failure (TOC, 2020A).

Thanks to a cooperation with two other organizations, TOC later came with an updated prototype, the “System 001/B”. After one year of testing, TOC stated on 3 October 2019 that its self-contained prototype succeeded in passively capturing and concentrating plastic from the GPGP using the natural forces of the ocean. This was the first true success since Boyan Slat presented his ideas in 2012 (TOC, 2019).

Additionally, TOC recycled the captured plastics into valuable goods: it turned them into sunglasses, a durable and useful product. This entrepreneurial activity is crucial to ensure future operations, as potential profit will be fully reinvested and, thus, completed the infinite circle (TOC, 2020B).

The adjustments in the prototype were incorporated in the newly designed system (002), that requires comprehensive examination and modelling before becoming the next full-scale clean-up system (TOC, 2020). Ultimately, “a fleet of systems” would be necessary to be able to clean up the entire GPGP and smaller plastic patches” (TOC, 2020A).

Furthermore, TOC is “looking to expand [its] operations all over the globe to help tackle the 1000 most polluting rivers, five years from the commencement of the scale-up phase” (TOC, 2020A, p.8). Replying to the criticism, TOC not only acknowledges plastic source reduction as important, but also strives for action.

Fig. 2: A seagull holding a plastic package in its peak (Ingrid Taylar, 2016).

Related articles

Bibliography

ABN AMRO (2014, 11 July). Seeds faciliteert succesvolste crowdfunding voor non-profit organisatie. Retrieved 30 November 2020, from https://www.abnamro.com/nl/newsroom/nieuws/2014/seeds-faciliteert-succesvolste-crowdfunding-voor-non-profit-organisatie.html

Dees, J.G. (2001, 30 May). The Meaning of Social Entrepreneurship. Downloaded 7 December 2020, from https://centers.fuqua.duke.edu/case/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/03/Article_Dees_MeaningofSocialEntrepreneurship_2001.pdf

Franeker, J.A. van & Kühn, S. (2018, 13 September). The Ocean Cleanup. Downloaded 6 November 2020, from https://www.wur.nl/upload_mm/0/0/a/3f5469b5-3e79-423f-a947-80b5a5b06c1a_FAQ-OceanCleanup2018_finalNL_CH-JAF.pdf

Geyer, R., Jambeck, J.R. & Law, K.L. (2017). Production, use, and fate of all plastics ever made. DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.1700782

Jambeck, J.R., Geyer, R., Wilcox, C., Siegler, T.R., Perryman, M., Andrady, A., Narayan, R. & Law, K.L. (2015). Plastic waste inputs from land into the ocean. Science, 347(6223), pp.768-771. DOI: 10.1126/science.1260352

Lebreton, L., Slat, B. […] Brambini, R. & Reisser, J. (2018, 22 March). Evidence that the Great Pacific Garbage Patch is rapidly accumulating plastic. Retrieved 6 November 2020, from https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-22939-w

Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management of the Netherlands (2018, 6 June). Convenant tussen de Minister van Infrastructuur en Waterstaat en The Ocean Cleanup betreffende de inzet van systemen bedoeld om plastic op volle zee, dat drijft in de bovenste waterlagen, op te ruimen. Retrieved 6 December 2020, from https://zoek.officielebekendmakingen.nl/stcrt-2018-31907.html#d17e790

Rijksoverheid (2016, 29 November). Waterinnovaties in Nederland. Downloaded 6 November 2020, from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/binaries/rijksoverheid/documenten/brochures/2016/11/29/waterinnovaties-in-nederland/Waterinnovaties-2016.pdf

Rochman, C. M. (2016). Strategies for reducing ocean plastic debris should be diverse and guided by science. Environmental Research Letters, 11(4), 041001. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/041001

Sherman, P. & Sebille, E. van (2016). Modeling marine surface microplastic transport to assess optimal removal locations. Environmental Research Letters, 11(1), 014006. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/11/1/014006

Slat, B.D., Arens, E. […] Zuijderwijk, N. & de Sonneville, J. (2014, 3 June). How the oceans can clean themselves. A feasibility study. Downloaded 30 November 2020, from https://ds1.static.rtbf.be/article/pdf/toc_feasibility_study_lowres-1401893379.pdf

The Ocean Cleanup (2015, 30 June). Annual Report 2014. Downloaded 30 November 2020, from https://assets.theoceancleanup.com/app/uploads/2019/04/TOC_2014_Annual_Report.pdf

The Ocean Cleanup (2017, 3 May). THE OCEAN CLEANUP RAISES 21.7 MILLION USD IN DONATIONS TO START PACIFIC CLEANUP TRIALS. Retrieved 12 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/press/press-releases/the-ocean-cleanup-raises-217-million-usd-in-donations-to-start-pacific-cleanup-trials/

The Ocean Cleanup (2018, 8 September). THE WORLD’S FIRST OCEAN CLEANUP SYSTEM LAUNCHED FROM SAN FRANCISCO. Retrieved 6 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/press/press-releases/the-worlds-first-ocean-cleanup-system-launched-from-san-francisco/

The Ocean Cleanup (2019, 2 October). THE OCEAN CLEANUP SUCCESSFULLY CATCHES PLASTIC IN GREAT PACIFIC GARBAGE PATCH. Retrieved 13 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/press/press-releases/the-ocean-cleanup-successfully-catches-plastic-in-great-pacific-garbage-patch/

The Ocean Cleanup (2020A, 9 June). Annual Report 2019. Downloaded 6 November 2020, from https://assets.theoceancleanup.com/app/uploads/2020/06/Annual_Report_2019.pdf

The Ocean Cleanup (2020B, 24 October). THE OCEAN CLEANUP INTRODUCES FIRST PRODUCT MADE WITH OCEAN PLASTIC POLLUTION. Retrieved 13 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/press/press-releases/the-ocean-cleanup-introduces-first-product-made-with-ocean-plastic-pollution/

The Ocean Cleanup (2020C). About – The impact of the cleanup. Retrieved 13 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/about/

The Ocean Cleanup (n.d.A). THE FIRST PRODUCT MADE WITH PLASTIC FROM THE GREAT PACIFIC GARBAGE PATCH. Retrieved 7 December 2020, from https://products.theoceancleanup.com/

The Ocean Cleanup (n.d.B). FAQ – How will you clean up 50% of the plastic in 5 years? Retrieved 16 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/faq/

The Ocean Cleanup (n.d.C). Can you provide an overall solution to ocean plastic pollution? Retrieved 17 December 2020, from https://theoceancleanup.com/faq/can-you-provide-an-overall-solution-to-ocean-plastic-pollution/

United Nations (n.d.). Goal 14: Conserve and sustainably use the oceans, seas and marine resources. Retrieved 7 December 2020, from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/oceans/