February 16, 2022

The importance and the beauty of mountain meadows lie in their high naturalness and for being perfectly inserted in a natural setting of high value, both from an ecological and cultural point of view. Over the centuries, traditional farming practices have shaped these environments, creating ideal habitats for the life of numerous animal and plant species. And here is where the role of man comes in as key element. As much as man has shaped mountain meadows in his favor and in favor of nature, he has also destroyed them. Since the second half of the twentieth century, the consolidation of intensive agriculture methods, urbanization and the abandonment of many disadvantaged farming areas have accelerated the loss of these habitats and hence the organisms associated with them. However, if this phenomenon is rather pronounced and worrying in the lowlands – resulting into the near total loss of meadows characterized by high natural value – it can still be recovered in hilly and mountainous areas [1].

Particularly in Trentino, the maintenance of a thriving livestock sector in the last decades has been fundamental for mountain meadows conservation. Moreover, meadows maintenance has been promoted for a long time also thanks to substantial public funding provided by both the Province of Trento and the European Union [2].

In this sense, technical terms must be clearly defined and distinguished. Meadows are technically divided into (1) natural meadows: naturally created and composed of native species; (2) semi-natural meadows: artificially created with native species and (3) artificial meadows: artificially created with genetically selected species.

When the need of renaturalizing an environment leads to meadow restoration, the creation of a semi-natural meadow is often an excellent option. Yet rather than restoring them, meadows should first be preserved and protected.

Figure 1: Safeguarding and protecting mountain meadow cenosis is essential to preserve landscape, farming and cultural features of the territory. (Author. Giazzera – Monte Pasubio (Province of Trento), July 05, 2020).

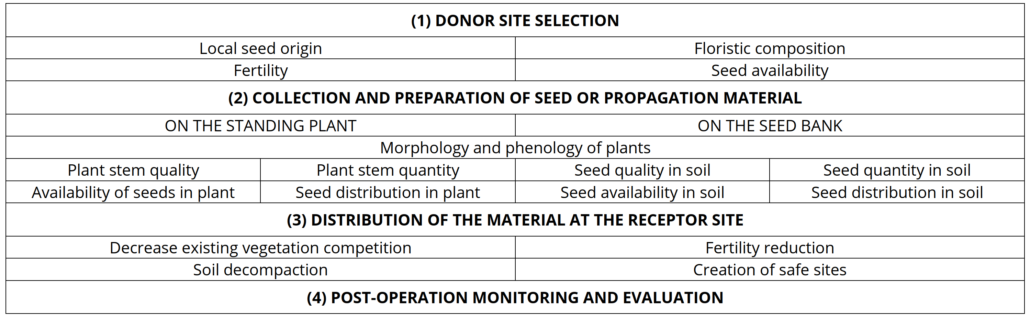

Research on meadows cenosis and its ecological restoration is particularly advanced in the Alpine area and, at least in Trentino, now implemented at a large scale [3]. The restoration process takes place in four phases: (1) choice of the donor site; (2) collection and preparation of the seed or propagation material in different forms (green grass, hay, hayseed from brushing machines or combine harvesters); (3) distribution of the material on the receiver site; (4) evaluation in retrospect of the success or failure of the process (Table 1).

The choice of the donor site must necessarily consider the (local) seed origin, its floristic composition, fertility and availability. This requirement is particularly important to favor a sustainable evolution of the vegetation. Especially in environments with adverse soil and climate features and where local conditions are therefore prohibitive for the establishment of non-native species, the choice of local native seed varieties is the only solution.

In the last decades, some central European markets have moved in this direction, with Swiss, Austrian and German farmers and cooperatives specializing in the production of native seed mixtures. This, however, has not happened in Trentino or Italy in general, where the collection and selection of seeds from existing semi-natural meadows remains one of the few viable restoration methods. Additionally, this method is often the only effective one in environments with a high species and vegetation diversity [4].

Seeds are collected directly from the standing plant or through a seed bank. In both cases, the following factors must be carefully considered: the quality and quantity of the stems or seeds in the soil, the morphology and phenology of the plants, the availability, distribution in the soil and in-plant production of the seed.

Similar steps are followed when seeds are collected manually and then propagated with agricultural production techniques. Yet, there are some differences between direct collection and distribution on the receiver site, and the method involving agricultural production. Indeed, production time requirements lengthen the restoration process by some years because seeds must be propagated through several generations. Nonetheless, the total cost of a restoration process involving farming production is lower and is, today, the most cost-efficient method for large-scale ecological restoration of species-rich meadows. A combination of the two methods is often useful because not all species can be easily propagated with farming techniques and not all the desired species can be easily found and collected from the field.

The seed distribution phase at the receiver site ends the restoration process. Again, traditional agricultural techniques such as mechanic or manual seeding can support the process.

To properly evaluate the restoration process, the receiver site geography, climate and soil condition prior to the restoration must be characterized and the restoration objectives clearly defined. For a successful meadow restoration, the receiver site soil must be tilled to decrease the competition between the introduced seeds and the existing grass species, fertility must be reduced, when necessary, soil must be decompacted, and safe sites must be created, where possible.

Table 1: a brief summary of the four steps of a meadow restoration process.

Finally, consider that the public price list of Autonomous Province of Trento includes such restoration works in the following categories: L.07.10.0050 – SEEDING and L.07.10.0052 – GRASSING WITH HAY OR LOCAL GREEN GRASS [5]. In 2021, prices for restoration works carried out with native grass species collected through farming propagation or directly from existing meadows, were comparable if not lower than that the prices for works carried out with mixtures of genetically selected seeds.

Besides an increasing attention of all stakeholders towards environmental protection and ecological restoration of the meadow’s heritage, we hope for a more complete market collaboration to start a flourishing and easily accessible trade of native grass species also in our territory. The environmental implications would certainly be positive.

Bibliography:

[1] Scotton, M. & Cossalter, S. (2014). PRATERIE SEMINATURALI RICCHE DI SPECIE NELLA PIANURA VENETA. Distribuzione e valorizzazione negli interventi di inerbimento e restauro ecologico. Veneto Agricoltura.

[2] Scotton, M., Pecile, A. & Franchi, R. (2012). I tipi di prato permanente in Trentino: tipologia agroecologica della praticoltura con finalità zootecniche, paesaggistiche e ambientali. Fondazione Edmund Mach.

[3] Zenatti, S., Gottardo, L. & Scotton, M. (2016). Restauro ecologico di praterie seminaturali tramite distribuzione di erba verde: l’esempio di Canal San Bovo (TN). Dendronatura, 37 (1), 49–58.

[4] Scotton, M. (2009). Semi-natural grassland as a source of biodiversity improvement–SALVERE. Proceedings of the International Workshop of the SALVERE. Raumberg–Gumpenstein: Agricultural Research and Education Centre.

[5] Provincia Autonoma di Trento (2021). ELENCO PREZZI 2021 [Online; in data 15-febbraio-2022].

Cover- and preview image: mountain meadow at Giazzera – Monte Pasubio (Province of Trento, Italy), July 05, 2020. Author.